15 July 2022

Acclaimed ensemble Forced Entertainment joins forces with DT+

Talia Rodgers

Head of Higher Education, Digital Theatre+

In 2016, Forced Entertainment (FE) – a long-running UK-based theatre and performance company – were the recipients of the lucrative International Ibsen Award, following in the footsteps of legends of the theatre such as Peter Brook, Ariane Mnouchkine and Heiner Goebbels.

The Ibsen Award by its own description “honours an individual, institution or organization that has brought new artistic dimensions to the world of drama or theater” (my emphasis). Forced Ents, as they are universally known, was the first ensemble – though not the last – to be awarded the honour.

It was a significant marker for the company who had established, as Catherine Love writes in her invaluable Concise Introduction to the company for Digital Theatre+, “an outsider position that has remained key to the company’s identity”.

Outsiders? Well, their collective mission has been to reinvent theatre “to reflect the times we are living in”, exploring contemporary urban life via an entirely new form of performance – that “new artistic dimension” the Ibsen Award seeks to celebrate.

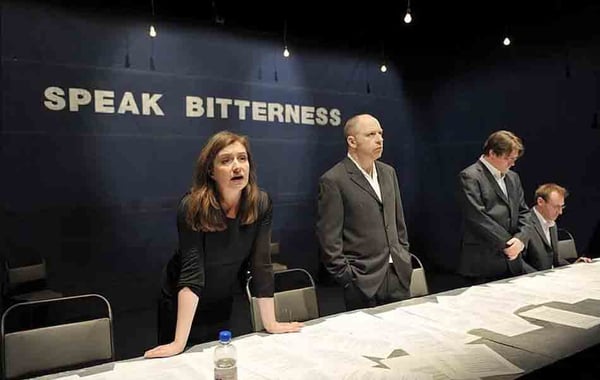

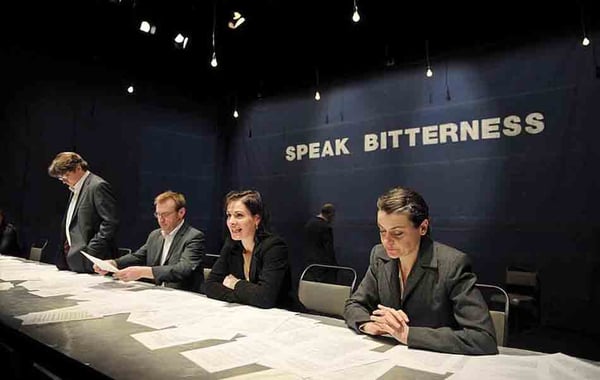

Forced Entertainment’s trademark collaborative process gathers together images and references from popular culture which they work on over many months of devising and discussion. Their work is frequently described as “post-dramatic”, eschewing linear narrative conventions such as character and plot. They experiment with the shape, form and even the duration of performance – one of their shows, Speak Bitterness, exists as a six-hour performance/installation, the first two hours of which we now have on Digital Theatre+.

Speak Bitterness © Hugo Glendinning

Speak Bitterness © Hugo Glendinning

As the FE website states:

“The essence of Speak Bitterness is a line of people making confessions from behind a long table. Occupying a brightly lit space, the performers take turns reading from the text that is strewn across the table. The litany of wrongdoing to which they confess ranges from the big time of forgery, murder or genocide to nasty little details, such as reading each other’s diaries and refusing to take the dogs out for a walk.

First presented in 1994, Speak Bitterness has subsequently been shown in both theatre and durational versions, the latter lasting up to six hours and allowing the public to arrive, depart and return at any point. An exhaustive catalogue, the text draws on the diverse cultures of confession in, for example, contemporary chat shows, churches and show trials. Dressed in suits, the performers compete to confess the most horrific, amusing or convincing things. Speaking softly, they meet the gaze of the audience (who are partly illuminated), drawing them into direct and intimate contact.”

The word “intimate” is key here. My own reaction to the show when I saw it in a tiny theatre in Brighton back in the 1990s went from bemusement (and laughter – some of the juxtapositions between confessions are hilarious) to uncomprehending anguish. I wasn’t at all sure why it moved me so much – but I came to realise that the direct eye contact and use of the word “we” at the beginning of each confession somehow implicated us, the audience, in the crimes and misdemeanours being described on stage. We were witnessing these confessions but also part of them too.

There’s something about a FE show which rearranges one’s mental furniture, which can be both exhilarating and perplexing. As such it’s superb material for teaching students about what contemporary performance can be, and what it can do to its audiences. About how much more pliable and challenging live performance can be than “the well-made play”.

Speak Bitterness © Hugo Glendinning

Speak Bitterness © Hugo Glendinning

Of course, the biggest impact is live – when you’re up close n’ personal with the performers eyeballing you and there’s nowhere to run. But the subtle and complex aesthetic they weave is beautifully captured in these precious archival resources. Having them on Digital Theatre+ realises a long-held ambition and we’re excited to bring them to our subscribers.

Peggy Phelan, in her brilliant Foreword to Etchell’s now-classic book Certain Fragments (Routledge 1999), refers to Etchells’ own statement that the company has had “a long commitment not to specific formal strategies but simply to challenging and provocative art”.

Phelan writes:

“...inspired most directly by the remarkable example of The Wooster Group, some contemporary performance ensembles have begun to form a collective response to contemporary Western culture’s ‘long commitment not to notice’ the ethical responsibilities it has to its past... More recently formed companies have been interested in creating new texts and movement performances that obscure the distinction between fact and fiction, truth and dream.”

She goes on:

“Certainly avant-garde performance has a long and distinguished history of employing performance to ignite the conscience of an ethical observer. From medieval morality plays, to the Forum performances of Augusto Boal…. Some important western theatre has been dedicated to making explicit links between theatrical arts and social politics.”

As we make our way through this troubled new century to find better ways of achieving justice and equity, it has never seemed more important to be imaginatively inspired by adventurous artists such as Forced Entertainment.

Related blogs

How to rehearse Greek Tragedy, with Carey Perloff

Have you ever wondered exactly what goes on behind the closed doors of the rehearsal room? The...

Read moreBeyond actor training: the work of the late Alison Hodge

Alison Hodge – ‘Ali’ to everyone who knew her – was a remarkable actor trainer and a leading...

Read moreJavaad Alipoor on Rich Kids and creating digital theatre

Javaad Alipoor’s innovative theatre work sits at the intersection between politics and technology...

Read moreGet the latest teaching tips straight to your inbox

Explore free lesson ideas and inspiration, education news, teaching trends and much more by signing up to regular blog updates!

.jpg)